All in a Day's Walk

A month-long slow food walking performanceArchive for December, 2012

Winter solstice

It’s the winter solstice which is the event I now choose to celebrate – with food, conviviality, warmth, gifts – as my mid-winter festival of choice. (Not that I’m completely bah humbug about the big C – I’m even walking to Putley for carol singing tonight.) All in a Day’s Walk has thrown this into an even sharper focus this year – the presence of daylight (or not) has been very much present for me in my daily life in walking and even eating. Eggs – my precious only source of local protein – have been harder to come by, because the shorter days are also the reason why the hens on the farm are laying less. (A connection I hadn’t considered before.)

I’m not a very conscientious celebrant, but it feels important to mark this turning point – the ‘standing still of the sun’ – as I’m walking underneath it.

‘The great cosmic wheel of the year… the symbolic wheel of time is acknowledged here. Jul or Yule means wheel in Norwegian. Northern Europeans of our Celtic past believed this mystic wheel stopped briefly at this crucial point as one cycle ended and a new cycle of the sun began. It was taboo to rotate any wheels at the Winter Solstice, from cartwheels to butterchurns, as they waited for the return of the sun.

Evergreens are brought into the home at this time to represent everlasting life…Each of the evergreens has a deeper symbolism. Red holly berries represent the red female blood of life while the white mistletoe berries represent the the white semen drops of the life-giving male

There is an old tradition of making wheels of evergreens as we celebrate the wheel of the year turning once again towards the sun… ‘

Glennie Kindred (2001) Sacred Celebrations Glastonbury: Gothic Image

Over the past few days, my walking has allowed me to collect various evergreens and I make a solstice wheel from plaited ivy (Fownhope church wall, to be mildly subversive), holly (How Caple and Capler Camp – the iron-age hill fort above the farm), yew (Capler Camp) and mistletoe (Oldstone Farm orchard). I also make my first truly successful rye-spelt sourdough bread – coincidentally shaped into a wheel/ring so that it can cook more easily in my stove-top oven improvised from a cast iron casserole dish.

SLOW flooding

It’s the eve of the winter solstice which this year will be at 11:12 tomorrow. Ignoring the Mayan/world’s end predictions, I walk into the village to post some Christmas presents, through fields wetter than I’ve ever seen them, latticed by runnels and new rivers. Maybe this is the end of the world after all and this project is remarkably prescient but for a lost consonant: not so much slow food as slow flood.

Foolishly I decide to wear my wellies again which might keep my feet dry but have no grip. I fall twice before I’ve even reached the village and have almost made it to the shop when I slip coming off the slope into the rec ground and slide on my back, laughing, down the bank thick with wettest mud. I walk through the village like a swamp beast, much to the amusement of the Post Office queue where I stand, dripping mud onto the counter, making it worse in my pathetic attempts to clean it up, which only succeed in smearing it further.

The postmistress sympathetically wipes my parcel “It will cost more if you weigh it muddy…”. Then weighted down with mud and apple juice and cider I walk home like a cross child with my unbearably caked-in-mud arms held out stiffly to the sides gritting my teeth. I tell a friend about the fall-Post Office palaver and ask “Should I be doing a PhD in clowning?”. “Or drowning?” he responds.

Pasture and pasteurisation

Warming my freezing feet on the still-warm-from-night-before wood burner before I set on a walk to How Caple where I’ve arranged to meet Debbie and Will Edwards, organic dairy farmers just above one of the sweeping bends of the River Wye. I’m excited to talk to them, because I’ve had some informal conversations with Will in the past and always been hugely inspired by his take on farming organically ‘in nature’s image’ and his passion for unadulterated milk, local food and pasture-raised animals. Unfortunately, this means that that cows are, quite rightly, dried off for the winter. So I won’t be able to try any of their milk raw (I was hoping to work out if I still had an allergic reaction to it, or if raw milk – with all its enzymes in tact – would actually agree with me. And I was also hoping to make some raw butter for a solstice treat. But hey ho…)

I walk down under Brockhampton Court, and through Totnor Mill (below, which seems to have been moated by its own leat, hence the little bridge), where a small alpaca herd eyes me warily. Then along the bridlepath to How Caple, which brings me out past another mill (I’m still pretty fascinated by these)

Will and Debbie are kind enough to give me over two hours of their time in the middle of the day, when I know that they would normally be busy with the stock. And the conversation is intense and wide-ranging – from milk (and the evils of pasteurisation and homogenisation) to pasture, to organic systems, to climate change, to Offa’s Dyke, Archenfield and cultural heritage. And it even concluded with a conversation in Welsh (supposedly my native tongue, but Will – who has learnt – was far more fluent than me.) There is lots of food for thought here – on local food systems, and the dysfunctional infrastructure and paperwork of so-called traceability that makes it so hard – too hard – for Debbie and Will to sell their milk themselves locally where it would be ultimately and eminently traceable.

Edited highlights of our mammoth conversation will appear here soon! To be continued…

Solar and salad

Today I’ve arranged to talk to Chris from Caplor Energy – the renewables ‘wing’ of the farm business here where I live. They specialise in solar photovoltaics and solar hot water systems. As a renewables geek, I’m inordinately proud of living here, where pretty much every large south-facing roof is covered in panels and the water in our shower block and livery yard is solar-heated (even Merlin is a fan). And we have a 15kW Proven wind turbine. In terms of energy for this project, all my space-heating, water-heating, and cooking is being supplied by my wood burner, fuelled with local wood. But I’ve also ‘allowed’ myself electricity – for light and computer only – on the basis of all this local renewable generation, the largest array on the barn just above my head as I type. It’s not a closed-loop off-grid system at Caplor, but I’m curious to ask, if it were, how much energy of the farm business and community’s energy needs would be met by the renewable installations. Chris gives me a tour and answers my questions and I’m particularly interested to learn that it’s winter food storage (potatoes) that takes a considerable amount of the farm’s winter energy use. The edited highlights of our conversation are here (with the interesting noises-off of two of the farm blacksmiths working in their nearby forge!)…

Later I walk to the village to catch the last post and stock up on local apple juice, the sun already setting. As I cut across the rec ground, they’re cutting the grass and I’m trying to work out why it’s making me hungry. Then I realise the smell of the grass is making me craving the juicy greenness of summer salad…

‘So that we don’t carbon ourselves into oblivion’

This morning, I walk over to Yare Farm again to pick up some more flour. It’s a beautiful day to be out but I need to rush back because I’m interviewing Gareth Williams – farmer at Caplor and my landlord – just after lunch. There’s a rainbow out as I walk over to the farm office.

And I’m particularly interested in what Gareth has to say about local food, because we’ve had many informal, brief conversations about this in the past and the posters on his office wall might suggest this is something he has an interest in.

But he shares some unexpected perspectives with me in these edited highlights of our conversation which ranged from food, farming, floods, economies of scale and globalisation… COMING SOON!

Pedigree Phocle Herefords at Caplor Farm…

Old cider press in the barn…

Fownhope Farm Shop

The Fownhope Farm Shop has been my mainstay and local food hub since the start of this project. Conveniently located almost literally on my doorstep, there has been a farm shop selling local produce at Caplor for the past 6 years or so. Originally this was the farm’s own initiative with all the produce grown on the farm itself, supplying not only the shop but also local schools and restaurants. It then went through various iterations – including a local food and crafts shop staffed by farm residents – before being taken over this year by Dave and Elise Shuker. They now manage the polytunnel on the farm and also keep pigs and hens here, but they stock a range of produce from surrounding local food suppliers. Sourcing all the food locally is at the centre of their ethos, knowing exactly where and who it’s come from: their own eggs, honey from Brockhampton, apple juice from Carey Organics, their own veg (in season) supplemented by a range of vegetables from Aconbury, Allensmore, Bartestree, Holme Lacy and Stoke Edith. Before going for a walk with my friend Sue who is staying, I visit the shop today. I ask Dave to draw on my map the exact locations of the places where all the vegetables I’ve purchased so far have come from, so I can plan my walks there accordingly and maybe contact the producers. Below is an edited recording of one of our many conversations as I shop…

I do not know how to make moisturiser from a nettle…

Being hyper-aware of where my food (and energy) is coming from, I’m suddenly hyper-aware of the ‘away-from-here’ ness of all the things I use and need: the ‘consumables’ that I consider essential (to varying degrees) or at least have become accustomed to being able to use whenever I choose. I make a substantial list even from the first things I’ve used within an hour of waking that day:

Toilet paper (recycled, natch)

Toothpaste (Kingfisher, of course)

Toothbrush (Monte Bianco, saving the planet one toothbrush stalk at a time)

Shower soap (Weleda)

Deodorant (Weleda)

Toilet cleaner (Bio-D)

Surface cleaner (Earth Friendly Products)

Sponge (alas, from evil supermarket)

Board chalk (village shop)

Moisturiser (Burts Bees)

Matches

Baking parchment (If You Care, FSC-certified – REALLY)

It’s worrying that, even through the frisson of eco-smugness that could be attached to the ‘ethical consumer’ brand names (=fewer chemicals, minimalist packaging, biodegradable, hand-made by free-range unicorns on a guaranteed minimum wage etc.), there is still so much s t u f f here…

And then there are all the containers – glass, plastic, film, cardboard – they are squashed, poured or rolled into and around. In all their colourful (yet also, of course, tastefully restrained) plumage, they form a textured map of the complexity of our dependence on t h i n g s: products that I – for all my supposed knowledge about ‘eco-living’ – would have little idea how to make myself or replicate the effects of using only locally available herbs or chemicals. (A sudden pang of eco-inadequacy: I do not know how to make moisturiser from a nettle.) And our dependence on oil to package, transport and store them.

Through my focus on local food and my physical, pedestrian relationship to fetching it, I am suddenly acutely aware of all that is coming in to my home and all that is going out and the physical journey it made to reach here. And thinking like this, even my own home – a static caravan at present – feels suddenly alien, other, with no relationship to me, my making or the materials available in the local environment. It’s as if we’re all caddis flies from a littered river, surrounded by a constructed carapace of compulsively-collected detritus that is not of our making… I mourn suddenly my recently-taken-down-for-repair yurt – with its wooden frame (trellis walls (khana) and roof poles) made from a Herefordshire oak felled by the maker himself. I had never before considered the ‘home miles’ of the shelters we choose to live in.

Impractical as it would be (for me and the rest of humanity) I can suddenly understand the urge to live in a bender in the hills…

Sabbath

I’m going with a Friday sabbath today. No walk, just domestics which are time-consuming enough. But I do start to toy with the idea of making a map of the produce I’m using… I have an idea I want to do this in a studio space with a map of Fownhope projected vast on to the floor, the routes I’ve tramped to each food seller/source progressively filled in with produce or its peelings over the course of the day’s installation as the sound track of the people I interview plays continuously… a map of local food emerges as the OS base is progressively filled.

I start fantasising about using lentils for orange B roads like a Carl Warner foodscape. Shame they’re not local. But what a waste that would be…

‘We ate with the seasons…’

Today Alison Parfitt (of the Wildland Research Institute amongst many other things!) joins me: my first ‘official’ guest to accompany me on a ‘performance’ walk. I haven’t planned very well for her visit and can’t decide where to go… When she arrives, we look at the map together. She would like to be a practical help in search of food and has brought along a large backpack for the purpose. I’d like to take her on an enjoyable walk that takes in some of the more scenic Herefordshire countryside. We settle on a walk over the Marcle Ridge through (a few) orchards to Westons, the cider producers where I hope I’ll be able to buy apple juice, and Much Marcle shop for eggs.

It’s still (literally) freezing. I still have no water in the caravan and every single surface outside – even the spiders’ webs – is covered in hoar frost: microscopic needles of crystalline blossom.

Alison’s lively enquiry into my practice is equally sharp but I’m glad of her presence and clarity – an antidote to the cold and the insidious slowness – helping to thaw my mind and bring into focus what I’m doing. As we walk, she asks me about the background to the project, which I start to describe as arising from my fascination both with simple notion of a day’s distance in a day’s time and what it could be used to draw attention to, to bring in to focus, to measure or calibrate. Then, how layered on to this came the notion of sustenance and what emerged was the concept of ’embodied mapping: drawing a map with my feet of the area that sustains me nutritionally’ and the sadness that we can’t always lead the local life we aspire to when we live rurally, in the place where all this food is grown because the infrastructure is now missing. I’m thinking specifically about the wheat, oats and oilseed rape grown on the farm – I talk about the roaring dragon of the grain dryer which drives us [farm-dwellers] demented with its day-long droning whine throughout August only for the grain to be shipped away again and sold. To me this is ‘extraordinarily inaccessible food’ and I talk about the notion of loss which Alison then goes on to summarise far more articulately : ‘ yes, it’s a loss of understanding, a loss of connection, a loss because we’re no longer in control of our food… we don’t even know where it goes and what happens to it. So it’s disempowering, really…’

With Sollers Hope church in sight, Alison asks. ‘So what are we performing?’… I respond cautiously ‘We’re performing slow activism and slow food in some kind of sliding together of lenses I think. The idea was that the structure of these walks – walking to find food, walking to the producers of food (even it’s not where I bought it I have to be able to walk to where it’s produced) was about drawing attention to what is there and what is there no longer, facilitating discussion, debate and discovery. And carrying that knowledge with me to each new encounter’.

I’m not feeling very articulate today, so I’m delighted when (as we are climbing steeply up the Marcle Ridge) she finds a way of clearly describing the essence of my practice – tracktivism as walking performance which foregrounds environmental concerns – far more clearly than my own fumbling attempts to liken it to bas-relief and the notion of removing something that obscures to allow what is there to emerge. No, she says helpfully, ‘it’s more subtle than that. It [the environmental/political ‘truth(s)’] is not obscured by something ‘other’ that needs removing, it’s the practice which reveals what IS there…’

I like this. As we walk on, I wonder what is left revealed in our wake.

—-

We walk into Much Marcle where I buy eggs (Kynaston) and juice (Aylton) from the village shop and record an interesting encounter with the shopkeeper, sharing his wonderful childhood reminiscences of rural life and local food in Oxfordshire where his father managed many gardens and allotments and they ‘ate with the seaons..’:

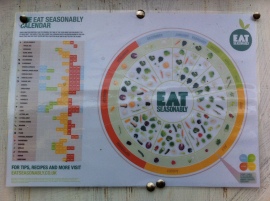

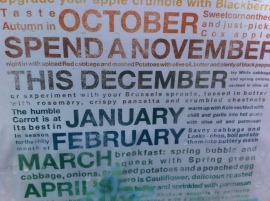

We then turn back on ourselves to call in at the Westons shop on the way home. Here they stock the full range of Jus single variety apple juices from sweet Egremont Russett and Worcester Pearmain through medium Coxs, Katy and Discovery to the dry Bramley Seedling (my absolute favourite). I intend to journey to Aylton later this month to talk to the Skittery family. Their juices have been my emergency energy food this month in the absence of fresh apples which I’ve not been able to source locally. This in itself points to another type of loss – the loss of knowledge of how to think slowly in the longer term and store our produce to eat out of season…

SLOW

In the caravan, my water is frozen today. (Picture’s from two years ago, but you get the idea.) Even though this only means walking to the very nearby showerblock to fill up buckets, bottles and kettle, I don’t have the mental capacity or calories to deal with this. I don’t walk today, any further than around the fields to break the ice on the three water troughs for the horses. Rough Patch – Banky Field – Rough Patch – Tacklizer – Rough Patch.

Cold, I am slowed down in every sense.

I expend my energy instead on the domestic: making bread, refreshing leaven, fetching and heating water, washing up, fetching wood, sweeping. It takes all my energy. I make a stew and feel better.

My s l o w n e s s makes me think how much I’ve read the term ‘slow’ in various contexts in recent times.

Slow food ‘a global, grassroots organisation with supporters in 150 countries around the world that links the pleasure of food with a commitment to the community and the environment. We work to reconnect people with where their food comes from and how it is produced so they can understand the implications of the choices they make about the food they put on their plates. We encourage people to choose nutritious food, from sustainable, local sources which tastes great.’

Slow pedagogy from Phillip Payne and Brian Whattchow (2008) ‘Slow Pedagogy and Placing Environmental Education in Post-Traditional Outdoor Education’ Australian Journal of Outdoor Education 12 (1): 25-38 ‘Time, and our experiences of it, warrants attention in ‘place’ pedagogies in outdoor education. Place typically involves the experience of a geographical location, a locale for interacting socially and/or with nature, and the subjective meanings we attach over time to the experience. Place, however, cannot be severed from the concept and practice of time, as seems to be occurring in the discourse of outdoor education. The way outdoor educators carefully conceive of, plan for, manage and pedagogically practice time may, in our view, positively facilitate an introductory ‘sense’ of place. We illustrate the under-theorised relationship of time and place in outdoor and experiential education via a case study of a semester-long undergraduate unit, Experiencing the Australian Landscape. It reflexively describes how two post-traditional outdoor educators working in the higher education sector have assisted pre-service experiential and outdoor educators to sense, explore, conceptualise and examine how ‘slow’ time is important in ‘placing’ education in nature.‘

Slow activism from Wallace Heim’s beautiful chapter ‘Slow Activism: Homelands, Love and the Lightbulb’ in B. Szerszynski, W. Heim and C. Waterton (eds.) (2003) Nature Performed: Environment, Culture and Performance Oxford: Blackwell 183-202

Slow = good Slow = better Slow = the answer?