All in a Day's Walk

A month-long slow food walking performanceArchive for weather

Talking Walking (or the Wisdom Teeth of Hindsight)

[I’m writing this with the benefit of hindsight. A whole year’s hindsight in fact. For reasons that will become clear below.]

On Friday 2nd August 2013, I walked nearly 30 miles from my then home in Lea (in South Herefordshire, mere metres from the Gloucestershire border) right across the Forest of Dean to the Green Gathering Festival at Chepstow racecourse. En route I had arranged to meet Andrew Stuck of Talking Walking – the dedicated podcasting website for ‘activism, art, gossip, interviews and news from the world of walking’ – to do an interview that would ultimately be made into a podcast.

He was travelling by train from London to Chepstow, and then planned to walk along the Offa’s Dyke path north of Chepstow. I was to join up with the path towards the end of my walk, so we hoped to walk towards each other and meet at the allotted hour. I would then be interviewed for TW. (It didn’t quite work out like that – though we did succeed in meeting – but more on that anon.)

It did not begin well, underslept and flustered, I set off at 8 am knowing I had about 24 miles to cover before I met Andrew, and very little spare time for getting lost built into the tight schedule necessary to ensure a timely rendezvous.

It was around this time that I’d more-or-less worked out that, on a 1:25,000 OS map, the span of my loosely-stretched hand aligned with a walk’s planned route was approximately an hour’s walking for me. But not allowing for getting lost, tracking back, talking to anyone or an overly wiggly/meandering path.

(I quite liked this one:one scale of my own though – a satisfying physical/temporal take on the one-inch-to-one-mile maps, for a walking geek and a map addict…)

Within half an hour, I had got hopelessly, dangerously lost in a field of >6ft high maize [I am 5 ft 1] that had been planted across the footpath. By the time I’d backtracked, run up a farm track and onto the road to take a longer, alternative route, I already knew that I would deeply regret agreeing to meet someone at an allotted time after 28 miles of walking. That is a lot of miles for mishaps… When the going (and the waymarking) was good, I did have a great sense of bounding through the Forest of Dean: this ancient hunting forest, freemining country, this “strange and beautiful place … a heart-shaped place between two rivers, somehow slightly cut off from the rest of England…” (as Dennis Potter described his home-place).

At other times, I was battling through overgrown undergrowth, with bare legs becoming so scratched and bruised that I eventually drew a sketch of the ‘map’ that the walk had left on me.

By mid-afternoon, Andrew – who had left London without a map and so was attempting to navigate his way from Chepstow along the Offa’s Dyke path by signposting alone – and I ended up in a ridiculous series of mobile phone exchanges. He was asking me to relay directions for him from my OS map, at the same time as I was trying to use it to navigate towards him. But our relative locations spanned either side of the enormous map sheet and so to respond to his requests, I was obliged, one-handed on the phone, to keep unfolding and refolding it.

We did eventually rendezvous – on the Gloucestershire Way, not the Offa’s Dyke path – and walked back towards Chepstow, where, once the calm of navigational certainty had resumed, we found a small meadow high up on the cliff edge of the Wye gorge to do our interview. The sound of drumming from the Green Gathering festival site at the racecourse on the opposite side of the river faded in and out of ear shot with the breeze.

We parted in Chepstow and I walked on alone to the festival, weary, scratched and ready for the wood-heated-water eco-shower that awaited.

***

What happened in the intervening three days is something of a blur – talking to ‘real’ activists: climate campaigners, road protesters, foraging experts, bee advocates, editors of ‘occasional land rights magazine’ The Land; and working in a cafe. I also had a very enlightening conversation with foraging expert Carol Hunt

I set off to return home on Monday 5th August, the penultimate day of the performance. I knew I’d got a long hard walk home and I also, foolishly, couldn’t shake the misperception that it would be ‘more uphill’ going north. I was also cumulatively tired – from the performance, the walking and the festival. So my spirits were dampened still further when there was a deluge of truly biblical, climate-change-freak-weather-type proportions within the first 5 miles: three hours of solid lashing rain, thunder and lightning. It was so wet that rain pooled inside my waterproof map case, having somehow managed to force its way through the almost imperceptible hole made by a thorn on the walk down.

Fortunately my phone, which I’d used to document the entire journey down, including film and audio, was safely zipped into the waterproof Gore-tex pocket of my waterproof Gore-tex coat. But it was not so waterproof as I’d thought. Water even managed to find its way to pool in there too. My phone switched itself off near Bream and refused to reawaken. Running late by the time I reached the middle of the Forest proper, I called in at the Speech House hotel (former hunting lodge and site of “Court of the Speech” for verderers and free-miners) and asked to use their phone to make a call to the dog sitter to let her know where I was.

I was bone weary by the time I returned to Lea. The cottage was eerily quiet, the dogs calmly pleased to see me, the dog-sitter having an evening nap upstairs. I put my phone in a box of rice, hoping for the best. Then I went to bed.

The next day, the final day of the performance, I rested. And waited anxiously for my phone to revive (funny how even eco-activists are so wedded to our technology). I was still hungry and looking forward to my ‘first supper’ the next day. But then on the last night, with no warning – but as if I’d finally earned it – a wisdom tooth chose to emerge. It was painful and I didn’t sleep well. So I woke the day after the performance concluded with the freedom to eat whatever I wish, and ironically found myself unable to eat at all.

[My phone never recovered from its ordeal, losing all my photo documentation from the last 60 miles of walking. So all that remains is the sketch of my scratched legs. Oh well. I suppose it could function as a tastefully restrained Richard Long/Hamish Fulton-esque ‘text work’ or similar: neither of them seem quite so concerned about obsessively documenting their walks through the use of technology. The very thought of either of them Tweeting or blogging (esp. en route) is actually quite a funny one.]

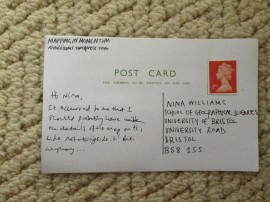

[Images of leg-scratch-map copied and later sent to PhD student Nina Williams for her Mapping in Momentum project]

Vegan roadkill

A walk through Dymock to Brooms Green, home of Charles Martell cheeses. I’ve been intrigued by this cheese-makers-cum-distillery ever since I’d heard my friend Hugh (himself of the inspiring artisan cider-producing Dragon Orchard) waxing lyrical about them back in December. I wasn’t eating cheese or dairy then of course due to a suspected allergy, but this time around and in the absence of allergy, their delicious nettle-wrapped May Hill Green has been very sustaining on long walks. I set off late today with a belly full of it. I haven’t called ahead to arrange a meeting, optimistically hoping to bump into someone when I arrive. Or simply for the walk to guide me into an encounter with someone else.

I don’t and it doesn’t. In fact, I barely see anyone closer than waving distance: two farmers mending a trailer and a lone dog walker. So much for talking activism today.

I pass through a sinister concrete bridge under the M50 that looks like it should house a 1960s concrete troll and join up with the Daffodil Way, round the edge of Dymock Forest. I pass an equally sinister looking mansion which instantly makes me think, with a goosebump frisson, of Sarah Waters’s The Little Stranger. For miles it seems to be watching me with coolly blank eyes, and I wonder why we anthropomorphise houses when really, they are just hemmings-in of space for us to shelter in.

In Dymock I find myself following the Poets’ Paths to Brooms Green. It’s not intentional. In fact, there’s something vaguely embarrassing about it. Perhaps this is because I’m always achingly conscious that walking seems to have a tendency to turn everyone into a navel-gazing poet or philosopher of varying degrees of awfulness, something I’ve been anxious to avoid through informing my walking practice with my environmentalism and other political concerns, of varying degrees of gentleness. By this, I mean that I’m permanently hyperconscious that, for all that I was at pains to put activism in tracktivism, I know there’s still nothing overtly, tub-thumpingly political about it. And inevitably, in the luxurious engagement with natural world that rural walking offers, the political is not present for me in every step. I am not a pilgrim. I can allow my mind and senses to wander.

What I remain conscious of, however, is that this is no rural idyll. These farmed landscapes are constantly changing and responding to the challenges of economy and climate. Less obvious, dramatic and dizzying than the melting ice-sheets to be sure, but still more fragile than we think. As our oil dependency continues and rural infrastructure falters, maybe we should all be walking these paths and writing bad poetry while we still have the chance? In less time than has passed since Edward Thomas, Robert Frost et al. were walking here, who knows what these landscapes will look like as a consequence not only of changing weather patterns and climate but also resource depletion and population explosion.

On the way home, I’m really hungry. I only brought a small sorrel and beetroot salad with me (no cheese or oatcakes), it’s 7 pm and I’ve walked about 17 miles, 5 more to go. Then I see on the side of the road a whole broad bean plant that’s been pulled up and dropped (by a creature? off a trailer? I’m not sure). Some of the pods are broken, but some are intact and I liberate the beans. Vegan roadkill, I think. At a green activists’ event earlier in the year, I’d been speaking on a forum about local food, revealing my epiphany that I’d suppressed my ethical concerns over killing animals to eat in favour my environmentalist understanding that pasture-fed (and finished) meat was a more carbon-neutral form of local protein (and very likely also a healthier one, than grain-fed meats). A vegan member of the audience had disagreed: with enough planning, she said, we were more than capable of growing enough beans to make enough protein to feed ourselves locally and ethically. The beans dont give me much oomph, but in my ongoing unease with eating meat and dairy, I wonder if she’s right.

Dams and damsels

I seem to be annoyingly addicted to alliterative blog titles, but I’m just going with it for now.

A walk to Ross-on-Wye and back with my friend Jessie, who is fasting for Dharma Day. It’s the first time I’ve walked with someone else this time around and the baking heat is a total contrast to the freezing hoar frost of my walk with Alison to Much Marcle in December. It’s also humbling to walk with someone who is intentionally and ungrumblingly fasting for spiritual commitment, rather than unintentionally, haphazardly and whingeingly for eco-activist performance.

Last night we sat around the fire in the gloaming and cooked Hope’s Ash and Crooked End beef steaks, picked and ate salad and herbs from the spiral, and, in the cauldron, boiled new potatoes from the field next door. Our own lettuce is growing faster than we can keep up; peas, beans and beetroot are nearly ready.

Today, on our way to Ross we pass through Hope’s Ash Farm again and bump into Robert on the yard. He beckons us over, stops the tractor and opens the door. There’s a slightly pregnant pause and I’m starting to worry that I’ve done something wrong when he says ‘I read your blog last night and it was the first blog I’ve ever read’. He seems to approve of it, and it’s given him some food for discussion (on veganism, dairy and meat) with an A-level student who is currently with them on work experience, heading for veterinary training. He asks me if I’ll have a chat with her about veganism which, he says unlike vegetarianism ‘which is easy’, he believes ‘really is hard’. So I do – ironically, standing with her in the pens of the day old dairy calves necessarily removed from their mothers so that we can drink milk, ‘the guilty secret of the dairy industry’ rearing its beautiful bovine head again.

Jessie and I walk on, talking about Buddhism, vows, our reluctant flexitarian meat-eating and its contradictions. We sprint, squealing, along the edge of a potato field, only just timing it right that we avoid a drenching by the rotating irrigator. Then we drop down and past the massive, industrial-scale Cobrey Farm: acres of fruit and pickers’ static caravans. We pass what I assume (from their accents and dress and our exchange of smiling, gesticulating nods) two European farm workers, also walking into Ross and playing music on their phone speakers as they do. It prompts us (Jessie and me) to discuss how more and more often (as Rebecca Solnit writes) we (culturally not personally!) think of walking as waste of time, a dead space to be filled with music on iPods or mobile phone conversations, neglecting the sensual pleasure that walking has to offer, not least as a mode of engagement with environment and self. We also talk about mobile phones, EMFs and the subtle body: are we living in a massive, global experiment that is scrambling our selves and our eco-systems, our bees and our pollinators and so ultimately our agriculture?

Dropping down into Ross and I make a beeline for Field Fayre, my local, organic, wholefood shop and recent joint runner-up (with Waitrose no less) as ‘organic retailer of the year’. I explain to proprietor David that this is the summer repeat of my winter performance (during which I’d first called in at the shop) and he talks me through the baskets and baskets of local produce. Because the shop is registered with the Soil Association, their remit is to sell certified organic produce, which means using European stock at certain times of year. But now, he says, it’s like ‘a dam bursting’: suddenly all the local producers have got everything:

We call in at delicatessen Truffles too on our way home – I want to thank them for their earlier generosity. They’re actually closed, but Richard opens the door in response to our persistent knocking and talks us through the huge range of Herefordshire produce they stock.

We walk back through Kingstone and stumble upon (if that’s possible), Bollitree Castle. We’re a bit disappointed that it appears to be a façade, but nevertheless I take photos of Jessie – with her spectacular Rapunzel-like mediaeval damsel hair – knocking on the door. When we get home, my partner tells us it’s the country home of Top Gear’s Richard Hammond. Surprisingly (for an eco-aware Buddhist) Jessie is a big fan. Later, I email her the pictures, laughing stupidly at my own subject line: ‘knock, knock, knocking on Hammond’s door?’

Heat and honey

An admittedly gruelling walk in 30 degree heat from Lea over May Hill to Highnam and Over Farm. It’s only about 25 miles, but it takes me 8 hours: I’m fast heading out but weighed down by vegetables, fruit and sun-weariness on the way back. Even as I set off in the morning, the waves of heat are palpable: we talk about the sun beating down, and all day I feel it like a slow hammer thudding me into the ground. I seem to be sweating all I’m drinking from my water reservoir straight back into the padding of my rucksack, so the weight is constant. Even ‘SPFd to ye max’ (as my friend Lewis sensibly advises – we have an acronym thing going on), my skin feels like it’s cooking. But, for all this whingeing, I’m not complaining. After the extreme rain and mud of December this is a welcome contrast. Though I do find myself musing about my canny knack of inadvertently planning my walking to coincide with extreme weather events – perhaps an unconscious climate change consciousness after all. That said, just the thought of ‘global warming’ in this heat makes me feel claustrophobic and nauseous. Walking across one particularly dry and scratchy field (I’m finding the long vegetation at this time of year is as difficult to walk through as December mud, plus I’ve developed an exaggerated allergic reaction to nettle stings) then grateful for momentary cool and shade passing through a thick treed hedgerow, I think about a future with less water, less shade, less space, less land area, more drought, fewer crops and more people to feed. It’s frightening…

Heading up towards May Hill, I pass a garden full of loganberries, fields of ripening oats, wheat and potatoes. Herefordshire is like a glowing, rounded expectant mother. This year feels like it will be a good harvest. But right now it’s locked in and inaccessible to me. And even when it bursts forth, how much of that crop will be shipped away from here to be ‘made’ or processed into food?

Striding up the lane, I pass a parked vehicle. ‘You’re off somewhere in hurry!’ a friendly passenger remarks. I explain I’m headed over to Over and have to get back within the day. I explain why and we get talking about local food. ‘You’ll be proud of me,’ she says ‘I took 100 litres of honey off my hives last week’. We then work out that it was her honey – ‘Happy Honey’ – that I’d bought at Brown and Greens two days ago, though she lives in Gorsley not here, so this really is coincidence. I’m curious about her perspectives on honey and the much-talked-about plight of the bees and she kindly agrees to share them:

I join the Wysis Way to walk up onto May Hill proper. Grasshoppers are chorusing in the long grass

I pass Taynton farm shop, the bottles of apple juice displayed on doilies (I thought they were extinct). I would like to buy some duck eggs but agree with the proprietor that in this heat ‘they’ll be cooked by the time you get home’.

I get lost after Taynton but find some bulrushes (reedmace) in a pond. I don’t pick any but I do know their rhizomes are a year-round source of carbohydrates (I’m not quite brave or hungry enough to try).

I pass High Leadon, Highnam, have a conversation with an elderly woman about cherries and am followed by curious cattle along the banks of the River Leadon.

A few miles off Over Farm and I know I’m on the right track: there is a strawberry-shaped helium balloon tethered above the pick-your-own fields. I contemplate picking-my-own and then decide, it’s a four hour walk back and I might save myself for today. Inside Over Farm market is a local food treasure trove: this is what they are passionate about and all the produce has a ‘food miles’ label. Satisfyingly, much of the produce is coming from the farm itself, so the labels read ‘less than 1 mile’ or ‘0’. I want to punch the air and whoop, but that’s a bit geeky. Then at the cheese counter (some more May Hill Green) I interview two young members of staff, Tom and Hannah. Both in their very late teens or very early twenties (I guess), they have some admirable perspectives and knowledge on local food, community and animal welfare. I ask them, is this typical of their peers?:

I slog home eating strawberries, grateful for the cool as the sun drops. As I curve around the contours of May Hill, heading directly west into the sunset, I pull the May Hill Green cheese out of my rucksack and ceremoniously eat the whole block. It’s rather poetic: eating a nettle-wrapped Gloucestershire cheese on May Hill with nettle stung legs.

Guilt and food miles

Guilt seems to be such a fundamental part of being human, that we are constantly needing to categorise it: Catholic guilt, Jewish guilt, Non-conformist guilt (my mother’s), survivors’ guilt, climate guilt and now, for me, (lapsed) vegetarian guilt. I experience plenty of the latter today.

As a former vegan (yes, I’ve worn that badge at the same time as self-reflexively laughing at the brilliant joke: ‘How do you know if someone’s a vegan?’ ‘Don’t worry: they’ll tell you’), I’m aware that lacto-vegetarianism is itself a half-way house in the compassionate farming stakes: even a very conscious and conscientious organic dairy farmer I know has admitted to me that the necessary removal of young calves from their mothers so we can drink the milk that is meant for them is ‘the guilty secret of the dairy industry’. So, I was already battling with some uncomfortable truths in being vegetarian. When I was diagnosed with a serious and potentially debilitating auto-immune arthritic condition 6 years ago and told it was highly recommended I eat fish, I did so, and felt both better and deeply hypocritical. When I completed the last performance of All in a Day’s Walk and heard about the carbon sequestration benefits of local, pasture-fed meat and how this offset methane emissions and provided a source of (local) protein that was not reliant on soya flown in from the other side of the world (and was an important part of maintaining diverse mixed pastoral/arable landscapes), I was forced to weigh up my environmentalism against my vegetarianism. The former won (it had always confused me that even some of the most ardent and eminent environmentalists I know are meat eaters) and I became a slightly reluctant flexitarian. (That is, occasionally eating only local, ethical, usually organic, free-range, pasture-fed meat.) I have also since read Jonathan Safran Foer’s pro-vegetarian treatise Eating Animals – perhaps a strangely counter-intuitive, retrograde choice of book after 22 years of vegetarianism – and, more recently Jay Rayner’s article about a a day in the slaughterhouse. So I remain deeply, deeply uncomfortable by the thought of being part of the meat industry and the killing chain, even in the most (oxymoronically?) ‘humane’ of abattoirs.

However, I am also hungry and in search of local food.

Today my partner’s son is dog-sitting for me, so I plan to do a decent walk to the nearest market town Ross-on-Wye as a reasonable starting point to encounter local growers and sellers. I am following the first part of a route I last walked during the winter performance to interview woodsman Dan at Deep Dean woods (the source of my winter fuel), now crunching and sliding through drying hay (as slippery as winter mud, I’m discovering).

Emerging from the woods below the poetically- (and, for me, autobiographically-) named Dancing Green, I encounter a group of workmen clearing a culvert and in conversation with someone who, from the back, I see is wearing an Open Farm Sunday T-shirt (a good sign, I now realise)… A little nervously – this will be my first true ‘tracktivist’ encounter with strangers to engage in conversation this performance – I stop and ask them if they know of any places selling local food, vegetables, eggs or honey and explain I am new to the area and what I am doing. As usual (because synchronicity is so surprising as to be unsurprising), it turns out this – food miles, local food – is a subject at the very heart of (who I later discover to be) Robert’s beef and dairy farming ethos, and one which he’s been explaining to a group of primary school children just that morning. Not only that but he tells me of a place just back through the woods selling eggs and honey. Success. And if I make a quick detour to get some (sadly they’re no longer selling either but I am kindly given one of the last remaining jars and shown around the magnificent vegetable garden) then head up to his farm on the hill above us, he will talk me through the food miles of the cattle fodder in his grain store. Here is the audio tour of our conversation which ranged from soya to fuel via sugar beet and weather:

Afterwards, and unable to carry a whole Hope’s Ash beef box home, I buy some frozen steak and mince from Rachel in the farmhouse and walk home as fast as possible before it defrosts in my rucksack in the afternoon heat. But as I go, I’m pondering again: I want to support these passionate, articulate local farmers but I’m carrying meat that has been finished with imported soya. If my only reason for eating (pasture-fed) meat is an ecological one, then I’m contradicting myself and might as well eat the imported soya myself (I was tempted, in the grain store). Then again, I think of the eggs that sustained me throughout the last performance and realise (as I hadn’t before) that most free-range hens are fed grain and layers pellets from well outside the county. And so the layers (no chicken pun) of our globalised local food infrastructure peel back and back. All these hidden food miles marching away from me as far as the eye can see – a lifetime’s walking in every mouthful… Food for thought and fodder for guilt.

Empathy and wild strawberries

Mads, a good friend and wonderful walking artist I know, recently introduced me to his concept of landscape e m p a t h y: the sensitive, receptive, mutually-supportive relationship we can allow ourselves to cultivate with place as well as people. I love this: it resonates perfectly for me as a much-needed explanation of the way in which the landscapes to which I’ve developed a commitment make a tangible tug on my heart strings, as if I’ve woven myself into them, viscerally. When I first left Aberystwyth for Herefordshire 10 years ago last spring, I felt like I was being unfaithful to Wales by developing a new relationship or love for the (as I saw it then) much tamer and more inhabited landscapes of this ancient border county. I’m ashamed to say I even scoffed at the statistic (true) that Herefordshire is the most rural county in England. To me rurality was directly equivalent to emptiness.

My first job here was a two and a half year stint as a project officer on the Herefordshire Rivers Lifescapes project, attempting to connect wildlife habitat mapping at a landscape scale, with community aspirations for the biodiversity enhancements they wanted to see locally, with the ultimate intention to facilitate community-led landscape-scale conservation. (It was very new, sexy and ambitious and only partially successful: it inevitably needed much more time.) After a full time dance-training hiatus, this was followed by a six year sojourn in local government as a landscape officer, with a colleague both passionate and knowledgeable about these intricate landscapes: ancient and planned, wild and cultivated. Her enthusiasm was infectious and slowly wore away at my deeply ingrained landscape snobbery (and ignorance) as did running, walking, riding and cycling across the county. One day, I was travelling back from a (landscape) conference and seeing the road sign for Hereford, felt a strange pang of both yearning and relief. Then, I knew: this county had surreptitiously made itself my home. Now, I know: (in my appropriation or interpretation of Mads’s term) I have landscape empathy with Herefordshire.

Key to this was my particular relationship with the eccentric, remarkable place that is Caplor Farm in Fownhope (South Herefordshire) where I have lived with my horse Merlin for nearly nine years. It’s a surreal community of people, horses and creatures, randomly juxtaposed in a range of dwellings (yurts, trucks, flats, caravans) to form a bizarre post-modern collage of humanimals. While it had been my intention to leave this year, to move back to Wales and reconnect my empathy strings for those landscapes, I had not expected that the first performance of All in a Day’s Walk would deepen my relationship – my empathy – with this place and reveal to me, as if in neon (or something more ecological perhaps), a vibrant, vital web of passionate and inspiring people I wanted to know better. I also had not expected to fall in love with one of them, nine miles down the road.

So I did leave. Just nine miles down the road, where I find myself now.

I’m a bit in limbo: after three weeks away being an aerial dancing ladybird in north Herefordshire, I’m only just landing. I arrive with a bag of sweaty dance clothes and even sweatier PhD reading, and most of my stuff is still at Caplor awaiting the end of this performance in a month’s time when my yurt will go up in the garden here. Merlin is going to join me next week. I know almost nothing about this area (Lea, Ross-on-Wye). But this time, I do have someone else’s ready-made landscape empathy to rely on.

So, my first walk of the project is with The Pack – my partner and our dogs – up the lane, past Rock Farm (potatoes and raspberries, when they’re ready) to Adam’s Cot (organic or local veg boxes) to arrange livery for Merlin. There, Martin tells me that due to the unseasonal spring, the veg is almost three weeks behind this year and they won’t have anything for me ’til the end of the month. Gulp. But horse livery sorted, we walk on past raspberry polytunnels (won’t fruit ’til next year), down Green Lane to Warren Farm (wheat and potatoes: not ready yet). With Cai, I walk on alone to Aston Crews in search of duck eggs. So far I’ve only drunk some Dragon Orchards apple juice (a gift for a talk at the Ledbury Food Group Ox Roast event) and eaten a head of elderflower (‘are you sure it’s not cow parsley?’ my partner, remembering a blog about a foraging malapropism on Ten Mile Menu that’s been a great source of amusement recently). We find some tiny wild strawberries in the hedge and I graze. Cai is curious but, as a hunter is largely unimpressed by my gathering. No duck or hens eggs left at Aston Crews. I’m hungry. And a bit scared.

So here I am walk-fasting again…

All in a Day’s Walk (Again)

All in a Day’s Walk is a month-long tracktivist walking performance. It was first performed in the winter, from 6th December 2012 to 6th January 2013. It is now being repeated in the summer, from midnight on 6th July to midnight on 6th August. During this time, I will live entirely within the distance I am able to walk away from home in a day, sustaining myself only on the food that is grown, harvested, processed and obtainable within this distance. I will walk as far and as frequently as I can, measuring out by foot the new limits of my new month’s (and new home’s) existence-subsistence-persistence. I will travel only on foot, accepting no lifts and using no public transport. I will not accept hospitality or food from hosts or visitors that does not meet these criteria. I will try to follow all the rules even if I can’t answer all the questions. And I will be curious about seasonal difference.

Tracktivism is about talking and listening, and I hope my walks will facilitate plenty of that: conversational encounters with the people I meet, either randomly on my route or pre-arranged at a specific destination… walkers, farmers, growers, millers, bakers, apiarists, artisan cider-producers, foresters, road-workers, yurt-makers, hauliers, butchers, bakers and candlestick-makers. We might talk about the weather. We might talk about talking. We might talk about walking. But we will most probably talk about f o o d , where it comes from, and why it matters…

It’s slow food meets slow activism meets slow performance. So, please take some time to meander through these pages if you wish, and leave some slow comments…

Jess Allen 06/07/13

Lea, Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, HR9 7JZ

Hooves and health

Merlin’s equine podiatrist comes to trim his hooves. He’s been barefoot – i.e. unshod – since April 2004 when I first became involved more intensely with the discipline of natural horsemanship and began to train as an equine podiatrist myself. This before dance training made me too precious about my body to want to consider standing underneath big horses all day, as they thrashed their legs around and I vainly attempted to hold onto the ends of them whilst wielding various sharp instruments (knife, rasp etc.)… But I remain a passionate advocate of ‘whole horse hoof care’, a relatively new (certainly, in the last decade or so) way of thinking about horses’ hooves as part of the whole beast and a key physiological marker of the health and well-being – nutritional/metabolic, cardio-vascular/musculo-skeletal fitness, even psychological – of the whole animal.

This may seem blindingly obvious, but traditionally, as British horse-owners, we have practiced a heartily devolved responsibility when it comes to our horses’ feet, entrusting their care – these distal points of their four precious limbs – almost exclusively to the farrier. (Not, as it happens, unlike our disconnected relationship to our food which is produced ‘somewhere else’ by ‘someone else’ and purchased from the supermarket, neatly packaged (in a protected atmosphere) in sterile plastic.)

‘No foot, no ‘oss’ the famous saying goes. And yet, few of us questioned if a man (for their invariably are) visiting every 6 weeks and nailing rigid metal to this (actually surprisingly mobile) proteinaceous tissue was perhaps the healthiest thing for the natural function of the foot. (Or even the less natural uses we might put it to – in that riding a horse is already inherently unnatural.) Suffice to say, it is now increasingly recognised that it is not. Though it is not as simple as simply removing the shoes. Barefoot horse husbandry – for high-functioning working/sport horses at least – requires a commited attention to the environment in which the horse lives, its nutrition and the ‘conditioning’ that one is prepared to do. In other words, if you want to drag your horse out of a muddy field once a week and go on a ten mile ride on the road or a cross-country competition, then you should probably stick to metal shoes. (Or get a quad bike. Or reconsider whether you have a respectful and meaningful relationship with that animal at all…)

My journey through the landscape of having a shoeless horse has necessitated and given rise to some big leaps of faith and understanding, not least that Merlin’s metabolic health – as evidenced by and echoed in his hooves – is in delicate balance, that it fluctuates seasonally, that British lowland pasture (largely now now rye-grass monoculture to maximise dairy production – and Caplor is a former dairy farm) is too rich in summer sugars for horses, whose digestive systems are still in time-lag, adapted to the dry grasses of the vast, arid plains where they evolved (and where their hooves were healthiest), and that hoof-infesting yeasts thrive in the warm, wet mud of climate-changed British winters.

If we listened to our own bodies as intently as I ‘listen’ to Merlin’s hooves, we might have a better understanding of our own nutritional – and seasonal – needs. And if we took greater responsibility for those needs – not handing them over to the supermarket ‘farrier’ – we might have a better sense of the whole systems in which we live, eat, breathe, participate.

Amazing, really, how I can now manage to bring every conversation, blog post or social encounter round to climate change, food and our relationship to it…

(And Debbie, Merlin’s trimmer, brings me some vegan Christmas cake too. Only 6 more days before I can eat it…)

Personal horizon (or Stoke Edith in search of swedes)

A New Year’s Eve walk in torrential rain to Stoke Edith (or, just beyond, to Newton Cross) where the swedes I’ve been buying from Fownhope Farm Shop come from. Today’s walk is just about walking (and talking if I encounter anyone, which seems unlikely in this deluge). Twenty-six days after I started and I’m only just now getting back to my original curiosity and key intention behind the project: to measure through the medium of walking the limits of my existence, beating the bounds of my ‘personal horizon’. For J. G. Ballard, who coined the term, this was based on sightlines (the limits of where he was able to see from the ground outside his home): only three quarters of a mile for him, in flat country. (According to psychogeographer Iain Sinclair, Ballard spent his year on a driving ban at home in Shepperton, refusing to take public transport and only walking three quarters of a mile in all directions, which meant he got to know his local area very well, and also that he ‘wrote more and better’, Sinclair says.) But for me it was more about ‘effortlines’: how far I was able to walk away from home and back in a day – preferably within daylight. (My original idea was to follow a simple formula of calculating how much light remained between setting off and dusk, then walk as far as I could in a more-or-less straight line for half of this time, then turn around and come back home.) This would of course depend not only on the time of year but also on the terrain, topography and, as it turns out, finding enough calories to sustain me.

It seems laughable now that, at the outset, I saw the local food I’d be eating as largely incidental – the walking would drive the work (and the talking, about food), but I had not considered quite how vital the food would be to fuel the walking. It has turned my idea of what a sustainable – and sustaining – art practice really is, completely on its head (as discussed in yesterday’s blog.)

So it’s both a revelation and a relief to have finally found a balance between calories in and calories out, and to understand in a very profound way how the landscape I’m walking and moving across is literally supporting me, nutritionally as well as ‘gravitationally’ (?). It seems a genuine embodiment of the former Countryside Agency’s Eat the View initiative, which was about connecting consumers to the countryside that provides for us.

This last week stretching ahead of me feels too short – there is too much to do, too many more people yet to talk to, in the food web that my encounters with others has uncovered. I also need to catch up and start ‘walking the food miles’ (as a friend succintly described the project) to all the places where some of the food I’ve been buying elsewhere (or on the farm shop here) is actually grown. So it’s also a relief to strike out away from home with a very physical purpose and rediscover the sheer exhilaration of crossing space. My determination beats even the weather, which is relentless. (My first exchange of the day is on the farm yard with monosyllabic but expressive cow-man Tom, who is also, like me, peering out of a small gap in his head-to-toe waterproofs. He gestures at the sky with his walking stick and says ‘Don’t think it’s going to stop’.)

I have almost given up taking photos of the mid-field rivers, floods, puddles and lakes that have appeared all across Herefordshire… almost.

But after a few miles, even I’m defeated. If I take pictures of them all, my obsessive documentation will slow me down even more than the mud. I also pass (depressingly) intensive broiler chicken sheds in Woolhope, the grain hoppers (unlocal grain? who knows) feeding straight into the windowless sheds in an automated system, so that even that simple connection between feeding – and acknowledging in the process – the animals we eat is lost. I walk over 9 miles beyond Stoke Edith to the main Hereford-Worcester road along the verge in incessant and depressing traffic to Newton Cross, then I turn around and come home. I didn’t see the swedes. But I was grateful for their sustenance and the miles they’d travelled. Every muddy last one of them.

And then, after witnessing the beautiful sunset, I buy luxurious duck eggs, Once Upon a Tree juice and vegetables from the Alumhurst Veg and Egg Shed

There’s no such thing as inappropriate clothing, only bad weather

When I first heard the (apparently Scandinavian) phrase ‘there’s no such thing as bad weather, only inappropriate clothing’ I immediately, gleefully and smugly adopted it as my new life mantra.

This winter, I’m not so sure. It doesn’t seem to matter how much Gore-tex I layer onto my body, the water is still finding a way in. Even in wellies. This does not make a December walking performance very comfortable. It slows me down – and not in a good slow-food-slow-activism way either. I’m not sure if drawing my own minute attention – through the immediate discomfort of soggy feet – to the changing patterns of weather and climate is particularly useful in an activism sense, but still…

I’m reminded of my conversation last week with Caplor farmer Gareth on his experiences of extreme weather events in Africa and Fownhope, and how his farming practices are, finally, changing: